Life as a fire lookout on the Payette Forest

BY MAX SILVERSON

The Star-News

Peering through Binoculars, Evan Lunning did not know if the white puffs he could see from his perch atop the Carey Dome Fire Lookout were wildfire smoke, or the low-lying clouds that often float through the Salmon River canyon.

Lunning had seen lightning strikes in the area the night before, and erring on the side of caution, he radioed the Payette Interagency Dispatch Center in McCall to report a smoke sighting. It was his second day on a summerlong posting at the Carey Dome lookout.

The next morning, he again watched through his binoculars as three smokejumpers parachuted down to extinguish what had grown into a small wildfire.

“My summer is made already, I got to see smokejumpers come in and jump out of a plane,” Lunning said. “It’s like watching a movie.”

Lunning, 29, was not sure what to expect from the job until that first fire.

“It definitely gave me a sense of purpose, that this is an important job to do,” he said.

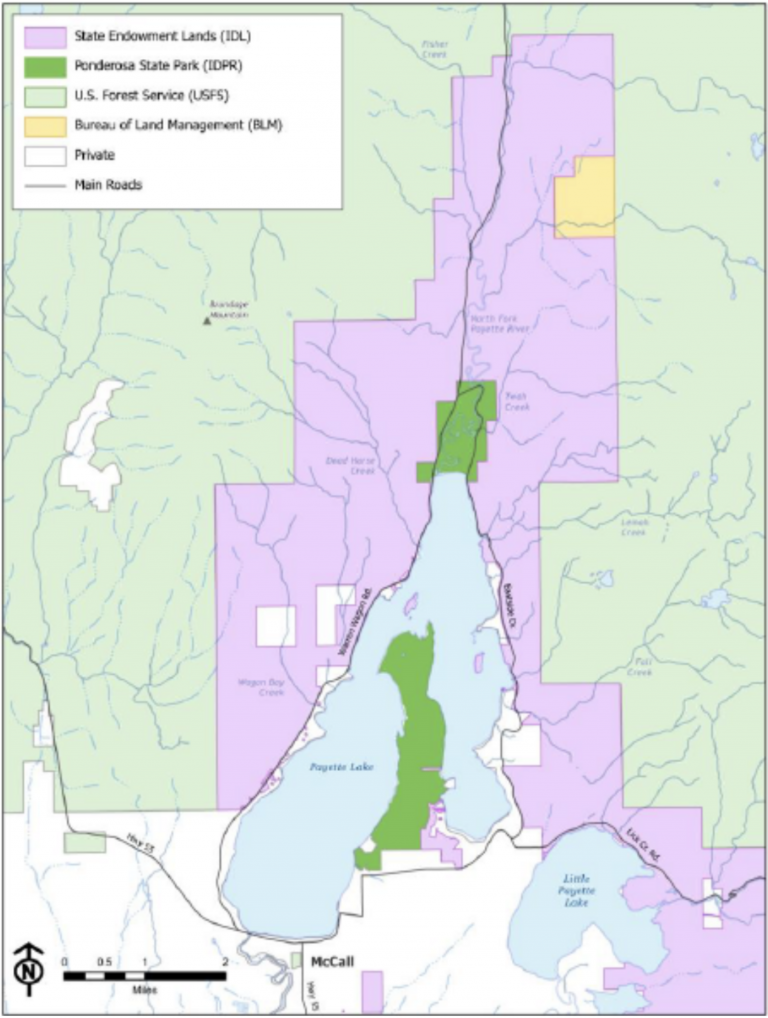

The lookout sits about nine miles north of Burgdorf Hot Springs atop Carey Dome Mountain. It is one of 11 active lookouts on the Payette National Forest.

The site includes a small one-room cabin that will be Lunning’s home for the summer. Serving as his office is an 85-foot-tall tower with a seven-foot by seven-foot room at the top set with windows on all sides, giving a panoramic view of the Payette.

The tower was built in 1935. It is the last remaining structure of its kind in service on the Payette.

Working as a lookout requires Lunning to spend about eight hours per day in the tower, scanning the horizon for smoke and reporting it so that firefighters can respond as quickly as possible.

The task will become increasingly important as conditions dry out over the summer, making fires more likely. Fires are often spotted in the afternoon, and following lightning storms, which cause most wildfires.

While this is Lunning’s first year on a fire lookout, some find the job irresistible, returning year after year to a life of solitude in the forest.

Daniel Moak, 38, is now in his 17th year as a lookout. This summer will be his seventh at the Williams Peak Fire Lookout about 22 miles northeast of McCall.

Unlike the cabin and metal tower at Carey Dome, the Williams Peak location resembles most mountaintop lookouts. The small cabin on the northwest ridge of the peak serves as both his home and office, with wall-to-wall windows on all sides.

For most of the year, Moak works as a professor of political science and public policy at Connecticut College in New London, Connecticut.

After a full academic year of teaching hundreds of students, Moak is ready for a break.

“I just enjoy being a little disconnected,” he said. “There is a very different pace of life, particularly compared to my other job.”

Daily water hikes

The benefits of living so remotely also come with challenges, including daily hikes to refill water from springs that are at least a half-mile away.

Lookouts often need to bring enough supplies for the entire summer, although on the Payette, food and other essentials are resupplied by helicopter every three weeks.

Regardless of the lookout, the post’s primary job is in the name: to serve as a lookout for fire starts and report them as soon as possible.

Once a lookout spots a fire, they radio another lookout to see if they can confirm a smoke sighting. If two lookouts can spot the same fire, they can pinpoint a specific location with an Osborne Fire Finder—a device located in every lookout station.

The device, which has been in service since 1915, includes a map and rotating sight that gives a directional bearing on where smoke is located in relation to the lookout. Readings from two different lookout locations gives fire dispatch a set of coordinates to where they can send firefighters.

If a lookout spots a smoke plume in a location that cannot be confirmed by a second lookout, it still reported, but often with less precise coordinates.

“Then you’re using your knowledge of the land and the topography to identify where it is,” Moak said.

Technology not up to task

There have been efforts over the years to replace staffed lookouts with cameras and other technology, but those have proven far less successful.

Fire lookouts are now often equipped with high-speed internet via satellite and some are within cell phone service, but even with reliable connectivity, cameras simply cannot replace a person.

“There is a huge value to actually having somebody out there,” Moak said. “There is a tendency to portray lookouts as this romantic bygone thing of the past…but it is a critical and perhaps the most effective and most cost-effective means of fire reporting.”

What looks like a fire through a video camera could just as easily be pollen, clouds or dust from dirt roads.

One camera atop a fire lookout on the Bitterroot National Forest had to be abandoned after a spider kept building a web across the lens.

Backcountry dispatch

As the only point of contact in the remote wilderness, Moak has been available to assist on several emergencies.

One involved an allergic reaction to a bee sting that could have been fatal if he was not within radio range and able to call a helicopter to assist.

Another time, Moak was the only person available to relay a 911 call from a campsite host reporting a domestic disturbance.

“That’s an aspect of the job that, while not necessarily the official job description, is a central part of what we do,” Moak said.

That role as a radio relay also helps during active firefighting operations, as lookouts can repeat messages from firefighters working in valleys, and otherwise cut off from communications.

The 11 lookouts posted to their mountaintop homes will continue scanning the terrain below through the end of fire season, which can last until October or November.